Irrational or Motivated? A Fresh Look at Confirmation Bias

Key Takeaways

Confirmation bias leads investors to favor evidence that supports their beliefs, neglecting crucial disconfirming information.

Self-interest and ideology play significant roles in how individuals interpret evidence, often shaping their decision-making processes.

Being aware of confirmation bias can improve investment strategies, encouraging a balanced evaluation of both confirming and disconfirming evidence.

Confirmation errors mislead the proverbial dog that believes his bark makes UPS trucks go away. The dog can test his belief by seeking disconfirming evidence.

How about not barking next time the UPS truck is in the driveway? If the truck stays in the driveway, that would be confirming evidence; however, if the truck leaves, that would be disconfirming evidence.

We use confirmation shortcuts when we examine evidence to confirm or disconfirm beliefs, claims or hypotheses. We use confirmation shortcuts well when we search for disconfirming evidence as vigorously as we search for confirming evidence and assign equal weight to disconfirming and confirming evidence.

We commit confirmation errors when we search for confirming evidence while neglecting disconfirming evidence, and when we assign less weight to disconfirming evidence than confirming evidence.

Confirmation Bias in Financial Decision-Making

Confirmation errors abound in investment behavior. One measure of this is the Bearish Sentiment Index, the ratio of the number of bearish writers of investment newsletters to the number of bullish writers.

Years ago, I was curious about a widespread belief that the index forecasts future stock market movements. Specifically, it was the belief that the index is a contrary indicator whereby high bearish sentiment forecasts stock market increases, and high bullish sentiment forecasts stock market decreases.1

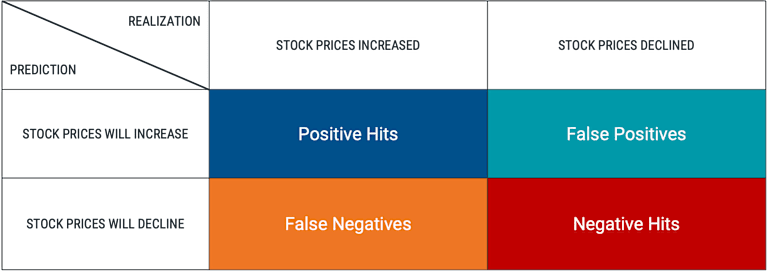

To properly test the belief that the Bearish Sentiment Index predicts stock market trends, we can place observations into four categories, as shown in Figure 1:

Positive Hits: Instances where stock market increases follow high bearish sentiment.

Negative Hits: Instances where stock market decreases follow high bullish sentiment.

False Positives: Instances where market decreases follow high bearish sentiment.

False Negatives: Instances where market increases follow high bullish sentiment.

We make confirmation errors when we assign much weight to the confirming evidence in the positive and negative hit categories, while assigning little weight to the disconfirming evidence in the boxes in the false positive and negative categories.

Figure 1 | Predictions of Changes in Stock Prices and Their Realizations

It turned out that the sum of positive and negative hits of the Bearish Sentiment Index was approximately equal to the sum of false positives and negatives, indicating no reliable association between the Bearish Sentiment Index and subsequent stock market moves.

The persistent belief in the usefulness of the Bearish Sentiment Index is likely rooted in the confirmation errors of users who count confirming cases and overlook disconfirming ones.

Reasoning Motivated by Self-Interest, Ideology and Other Factors

The tendency to commit confirmation errors is exacerbated by motivated reasoning. People are motivated to commit confirmation errors by self-interest, ideology and other factors.

In one study, students were told that they would be tested for an enzyme deficiency that would lead to pancreatic disorders later in life. The test consisted of depositing a small amount of saliva in a cup and then putting a piece of litmus paper into the saliva.

Half of the students were told they would know they had an enzyme deficiency if the paper changed color; the other half were told they would know they had a deficiency if the paper did not change color. The paper was such that it did not change color for anyone.2

Students who were told the unchanged litmus paper conveyed good news did not keep the paper in the cup very long. In contrast, those who were told the unchanged color reflected bad news tried to recruit more evidence. They kept the paper in the cup longer, placed the test strips directly on their tongues, re-dipped the strip, shook it, wiped it, blew on it, and, in general, quite carefully scrutinized the recalcitrant test strip.

Reasoning Motivated by Goals and Aspirations

Motivated reasoning likely underlies the belief that the Bearish Sentiment Index predicts future stock market moves. Investors who crave a method to predict stock market moves might be motivated to believe the index offers reliable stock market predictions. They count confirming cases and overlook disconfirming ones.

However, reasoning might also be motivated by goals and aspirations. I encountered such motivation in a student in my recent MBA investments course. The student, almost 50 years old, raced ahead to the section about options and started trading as a day trader.

I invited him to my home, served him coffee and snacks, and listened to his story. He knew the evidence showing the vast majority of day traders end up as losers, but he thought that he had found a winning method, especially when his first trade netted a $10,000 gain.

He said he only needed a $1,000 gain per day to live on. I found that he was motivated into day trading by his dissatisfaction with his career as a project manager. He aspired for a more satisfying career. I offered my empathy and explored alternatives to day trading as a means to reach his aspirations. I noted that an MBA would help him secure a more satisfying career.

The lesson I draw for myself as a teacher and offer to financial advisers is to explore motivations for confirmation errors. Teachers and financial advisers might best serve their students and clients by providing empathy and exploring prudent ways to satisfy goals and aspirations.

Authors

Consultant to Avantis Investors®

Explore More Insights

Michael E. Solt and Meir Statman. “How Useful Is the Sentiment Index?” Financial Analysts Journal 44, No. 5 (Sep–Oct 1988): 45–55.

Peter H. Ditto and David F. Lopez, “Motivated Skepticism: Use of Differential Decision Criteria for Preferred and Nonpreferred Conclusions,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 63, No. 4 (1992): 568–84.

The opinions expressed are not necessarily those of Avantis Investors®. This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as investment advice.

The contents of this Avantis Investors presentation are protected by applicable copyright and trademark laws. No permission is granted to copy, redistribute, modify, post or frame any text, graphics, images, trademarks, designs or logos.